Want to learn how to pray? Forget words. Forget about getting the right name for God. Forget fidgeting about how to sit or stand or hold your hands. Forget whatever you have been taught about prayer. Forget yourself.

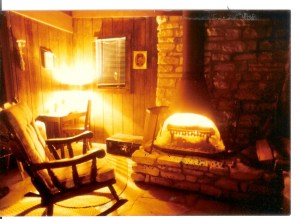

And go gaze upon something or someone you love. Look long and deeply at something which gives joy or peace –

that penetrating lime green of the spring woods, and the wet black branches like some ancient language of scribbles and runes scrawled all over the forest

the path of the sun, trailing like a golden ribbon across the floor, climbing up the table and tying itself neatly around your tea cup

the sleeping boy in his Superman PJs, smelling of grass and child sweat

Next: Let yourself be held there in your looking and wonder. Do you feel that subtle magnetic force that seems to gently grasp and suspend you before your beloved?

Breathe. Relax.

Notice what wells up in you and what recedes. Various feelings and thoughts – some positive, some negative. Simply observe the play of your inner life as you gaze upon beauty.

Notice the voice which says, “You need to get moving. There is a lot to do. Should I fix potato soup for supper? I really can’t stand that woman.” Keep returning to what you love. Allow your love and appreciation of this portion of the world draw you in to its Creator and Author, that pulse of the Spirit which animates all of existence.

For that is what Holiness is doing in the creation – luring us, catching us up, and reeling us into the Heart of Reality and Divinity through the things of this world. God threads us through and beyond what we love to deeper love and freedom in the realm of Grace that is called God’s kingdom.

Really. God will use anything, anyone to draw us into God’s self, God’s being, and into truth, into love, into amazement, and wonder. What draws you into this prayer will likely be something uniquely suited to you, your aspirations, your interests, your peculiar, and particular existence. So specific is God’s summons to you. So beloved are you by God.

All that is required is your consent – your yes, your willingness to take the bait, to bite into creation with appetite and hope.

After looking at God in this way for a while, a word or two, a spoken prayer may emerge from your heart. Something you want to say to God. Something you desire from God. Go ahead and whisper your words to God. Then be silent and listen.

A Peace will come and settle over you, a calm, perhaps, a gentleness, an assurance of some kind.

Afterwards, before you turn back to getting things done, do a little self inventory:

Have you changed in any way after this time of gazing? Is there a difference in how you are feeling or thinking? Is there something from this time you need to stay with or return to? What would you like to say to God about this time? What would you like to hear in response from God?

And this, my friends, is a prayer.

This is a way God speaks.

This is a way the Word Made Flesh calls our name.

This is a way we answer.

Other Praying Life posts on prayer you might enjoy:

Contemplation – Circling a Definition

Paying Attention and Taking Your Time