God is simplicity and one-foldedness,

inaccessible height and fathomless depth,

incomprehensible breadth and eternal length,

a dim silence and a wild desert.

So wrote John of Ruysbroeck in the 14th century.

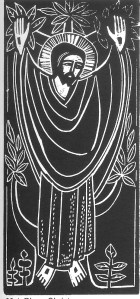

God is also a man, whose name is Jesus,

born in a middle eastern city,

of a woman named Mary.

Firmly anchored in time and space,

he walked the paths of Nazareth,

ate, and laughed, and loved.

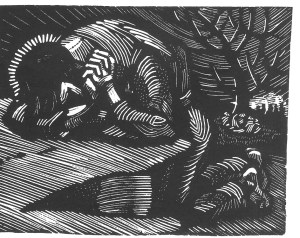

God is also this same man,

now beaten, bleeding, and dying,

executed on a cross.

For in Jesus

the Inaccessible Height and Fathomless Depth

had inserted

itself into

the messy specificity and limitation

of humanity,

and consented

to occupy

suffering,

injustice,

cruelty,

fear,

defeat,

So now, all that suffers, loses, messes up, and bleeds finds welcome in that dim silence and wild desert of the cross. All that is lost or broken is gathered and folded into the height and depth and breadth and length of God. Every precious particle of God’s making is held with infinite tenderness in the simplicity of love.

There are moments, days, even years for some, where the work of solitude involves suffering. Alone with God, we are presented with painful truths. We are refined and purified. We gradually learn to be present to God, not on our terms, but on God’s terms in the context of our own specificity.

This is the work of letting go and letting be. This is the journey of ever deepening faith and radical trust. This is the door that sets us loose to roam forever free.

During the observance of Holy Week, the specificity of God made known in Jesus, enters into the lonely anguish of surrender to the terms of his Father. The one who has been surrounded by crowds and encircled by his chosen disciples, makes the solitary journey into death to return to the heart of all being.

We find an account of this journey in the gospel of Mark. Mark’s gospel is characterized by a simple, direct, unpretentious style. The gospel has an urgency about it. Mark’s frequent use of the dramatic present tense contributes to the immediacy. The emphasis is on the action – the deeds and words of Jesus – as he confronts and responds to the religious establishment, the disciples, and the crowds. This action moves compellingly to the crucifixion. The story unfolds in a hurry, as though the very presence of Jesus has set in motion forces which lead inevitably to the cross.

Then at the cross, in striking contrast to the preceding scenes, Jesus becomes the receiver of the action in total surrender. The syntax changes from active voice to passive voice, as the Greek word, paradidomai, appears more and more frequently. Paradidomai means handed over, or to give into the hands of another, to be given up to custody, to be condemned, to deliver up treacherously by betrayal. This is the same word the gospels, as well as St. Paul, use repeatedly to describe the crucifixion.

As the resurrected Jesus tells Peter on the lake shore, there comes a time when we will be carried where we do not wish to go. (John 21: 18) Then we find ourselves being handed over to our life circumstances, the limits, sins, injustices, and frailties of human existence.

At the cross in Jesus the Limitless, Inaccessible, Unfathomable God makes things very plain, very simple:

Watch me. Trust me. Do it like this. All is forgiven. Surrender. Allow yourself to be carried into darkness. There is a place beyond your knowing or naming, where I am and you are. Follow me.

All transformation, all redemption require moments such as these:

the passivity of the seed buried in the earth,

the passion of love poured out to the last dregs for the beloved,

the prostration of oneself in the dim silence and wild desert,

where all things are born anew.

The moral revival that certain people wish to impose will be much worse than the condition it is meant to cure. If our present suffering ever leads to revival, this will not be brought about through slogans, but in silence and moral loneliness, through pain, misery and terror, in the profoundest depths of each person’s spirit. Simone Weil

Solitude Practice:

- What do you need to surrender, let go of, or let be this week?

- Not all, but much of our suffering may be tied to our defiant resistance to letting go and refusal to accept the suffering of self denial. Do you agree with Simone Weil that broad social change could be gained, not by imposition of morality, but through the struggle in the depths of individual souls?

- What is it like for you to shift from being the prime mover and actor in your life story, to becoming the receiver of the action of others? How might God be handing you over this Holy Week?

- Is there a relationship between your consent to being carried where you do not wish to go and experiences of healing and redemption in your life?

Next post in this series – Exploring Solitude: Leaving solitude, gone to Galilee.

______________________________________

News for Praying Life Readers!

I am leading a workshop in April here in Topeka, KS. Hope to see some of you there!

Look and See: Nurturing a Shining, Festive Life of Prayer

Saturday, April 21, 2012

8:30-12:00

$20.00

First Congregational Church

1701 SW Collins, Topeka, KS

Please register early to assure a place by calling or emailing First Congregational UCC. 785-233-1786; info@embracethequestions.com

Related articles

- Exploring Solitude: The Wild Things Within (theprayinglife.com)

- Exploring Solitude: Learning to Be (theprayinglife.com)

- Exploring Solitude: Why Bother? (theprayinglife.com)