Here is what I want you to do:

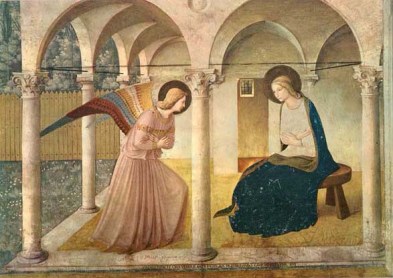

find a quiet secluded place so you won’t be tempted

to role play before God.Just be there

as simply and honestly as you can manage.The focus will shift from you

to God,

and you will begin to sense his grace.

Matthew 6:6 MSG

Nobody is watching. Go ahead. Be yourself. Relax. You walked off the stage of your life performance and the audience has all gone home. Feel the weight of that armor, the heavy guard you wear night and day about your shoulders and neck? You won’t need it now. Lay it down.

Oh. Wait a minute. It appears that not all of that audience has gone home. A few hitched a ride into the hermitage in your mind. Take that broom in the corner and chase them out. As long as you do not invite them to sit down, and then start feeding them milk and cookies they will leave. Their harping and commenting will begin to sound sillier and sillier to you in the context of your wilderness.

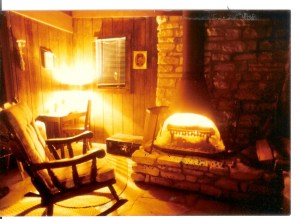

Go ahead. You can’t hurt the furniture here. Put your feet up and settle into that delicious and utterly joyful place of being yourself, your true self.

A wonderfully freeing aspect of solitude is that nobody cares what you look like. Nobody is there to comment upon, critique, approve, or disapprove of your actions, attitudes, words, mannerisms, personality preferences, and quirks. No one has expectations of you or needs they want you to meet. No one is going to call or drop by unannounced.

Go ahead. Remove that hot stuffy mask.

We have a public face we present to the world. In some cases it is brittle, artificial, and controlled. We put on the mask of a happy person, a competent person, a funny person. But a mask is a limited snap shot of the person we really are, which may include being happy, competent, and funny, but who we really are also has depth, texture, responsiveness, and spontaneity, which masks cannot communicate.

When the face we present to the world is the same nuanced face within us, people call us authentic and real. What we show on the outside has integrity with what is in the inside. The phoniness, pretension, and the effort of maintaining a façade are gone.

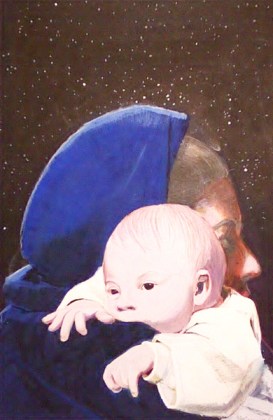

I loved taking people out to the hermitage. I would show them around the grounds and cabin, give them some orientation, and, leaving them alone for a few days, drive back to town. Then later, they arrived at my doorstep to drop off the trash, the empty water bottles, and return the key. When I opened door, I was amazed at the differences in the guests. The tension and stress were gone, and an ease and lightness filled their movements. And their faces, soft and smooth like a child’s, wore a refreshing, unguarded openness and simple presence to the moment.

After I spent a long period in solitude, a friend reported that I looked like the Velveteen Rabbit. “Worn and soft. Well loved, and real,” she said.

There is nothing like solitude for peeling off the layers of pretense and inviting a soul into deeper authenticity.

In the days of silence and company kept only with crows, meadowlarks, and the possum, who comes looking for food under the moon, one becomes aware of the vast amount of energy and time, which may be spent on building facades and presenting a particular face to the world. The hours of calculation and strategizing to strike the right note in a speech, the stress filled preparation and rehearsals to achieve a certain affect. We have all been encouraged to become marketers and publicists for our careers, our work places, and even our very lives.

Here relationships degenerate into a potential sale, or a possible connection to a step up the ladder. Social media invites us to fashion our lives on a global stage, where our preferences are watched and matched to product ads which pop up before us.

In contrast to the world of hype nothing is for sale in the wilderness. Further, in the wilderness your stuff and your “brand” start to become embarrassing — all that lipstick in your purse, the three jars of face cream, the books you lined up on the book shelf, those clothes you shopped for.

The wilderness around you takes on a depth, beauty, and fascination that cannot compare to that iPad you just had to have or that “outside the box, edgy high concept” project you have been working on. The world beyond your wilderness begins to seem artificial, crass, and out of sync with a deeper more profound rhythm.

Oh course, it makes sense that the natural world would inspire you to drop off what is unnatural and false in yourself – those postures and attitudes you take; that pride that you use to hide your vulnerability and need.

Besides, you are not going to fool that turkey vulture soaring over the pasture. He may be pecking at your bones one day and won’t give a damn about what kind of car you drove. The lake, teeming with turtles, bullfrogs, fish, and dragonflies is unimpressed with your credentials.

Yet a few creatures may be curious about your presence. There is nothing you have they desire. All they can offer you is their own mysterious being.

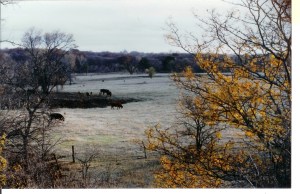

The cows, snuffling at the window, wake you at dawn. A large black angus is peering into the cabin. Her face is framed by the window and the chintz curtains.

You go out barefoot in your pajamas to shoo the cows back into their pasture. There are several mamas with their young ones. You stand still gazing at each other. You watch their massive ribs expand as they breathe, their dark eyes, and pink tongues. They watch you, seeing how your feet are getting damp in the dew, considering your breath, your two legs, and your white silk pajamas.

Your being interpenetrates with their being. A conversation and exchange occurs beyond words. Atoms shift, energy moves, recedes, and gathers in the spreading light. Then they turn, their hooves sinking into the damp earth, swishing their tails, and go back through the broken fence.

Nobody in the wilderness cares what you did last week. Or what you didn’t do. One of the calves looks back at you, slowly chewing grass, hanging out both sides of his mouth.

You feel you need to get right down on your knees in your pajamas and repent of something you do not have the words for.

Oh my God, forgive me for not seeing,” you pray.

Solitude Practice

- Do you find yourself caught up in playing a role or meeting others expectations and needs unnecessarily?

- What is it you let go of, when you let down your guard?

- How does being alone in nature help you be yourself?

- In what way might the wilderness call you to repentance, or seeing in a new way?

Next post in this series: Exploring Solitude:

So What Do You Do Out There All Day Long?

Related articles

- Exploring Solitude: The Wild Things Within (theprayinglife.com)

- Exploring Solitude: Deadly Acedia, or Too Bored to Care (theprayinglife.com)

- Exploring Solitude: Why Bother? (theprayinglife.com)

- Exploring Solitude: Where the Wild Things Are (theprayinglife.com)